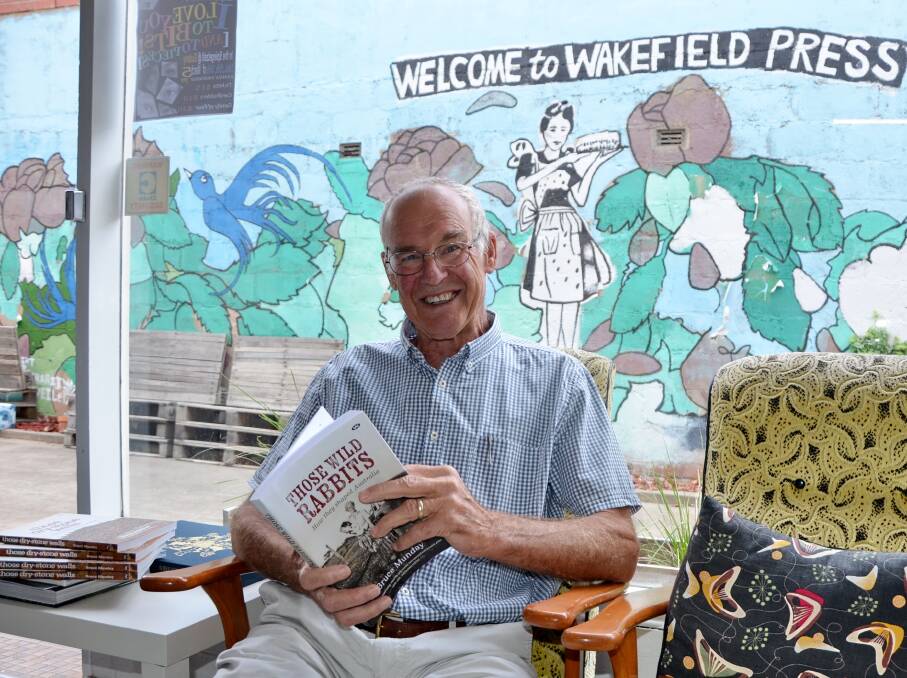

AUTHOR Bruce Munday’s new book – Those Wild Rabbits – is an in-depth look at the economic and environmental damage caused by rabbits, and also uncovers hidden figures in the fight against the pest.

Subscribe now for unlimited access to all our agricultural news

across the nation

or signup to continue reading

The book was officially launched at an event at Mount Pleasant on Friday.

“Rabbits are seen as cute and cuddly, which is understandable, but it is the wrong image for them to have, people need to know they do a huge amount of damage,” Bruce said.

“It’s not just economic damage but environmental damage as well. It’s hard to measure how much environmental damage they do, because we’ve never seen the environment without rabbits.”

A varied career path led Bruce down the writing route and to the release of his new book.

“I originally trained as a physicist but I always had a hankering to own a farm. In 1974 I moved to a farm between Mount Torrens and Tungkillo. It was just 121 hectares, but enough to keep me busy,” he said.

Bruce ran the property and taught part-time for a number of years.

“I was still teaching in 1997 when I started my own business as a communications consultant in agriculture and natural resource management,” he said.

“When working as a communications consultant, I did quite a lot of writing and editing, and while it was always technical stuff, I’d always liked telling stories.”

Bruce was interested in stone walls, because he had a lot on his Tungkillo property and that led to his first book, Those Dry-Stone Walls, which was first printed in 2012 and has been reprinted twice.

“While researching that book I came across a lot of information on rabbits. I’ve always thought there was a story to be told about rabbits in Australia, mainly about the trouble rabbits caused,” he said.

Bruce started working on the book in January last year, after sponsorship from the Foundation for a Rabbit Free Australia helped to get the book off the ground.

“One thing I particularly wanted to capture in the book was old-timers’ memories of what it was like in the time of plagues, before myxomatosis came in,” he said.

The history of rabbits in Australia goes back to the first settlers, who bought them out as food.

“They tried to farm them, but that failed, because as soon as they’d be let out, they’d be eaten by an eagle or another predator,” Bruce said.

There was no success trying to get the rabbit numbers up in Australia until 1859 when Thomas Austin introduced 24 wild rabbits to Barwon Park, near Geelong, Vic.

“He brought wild rabbits out from Scotland, and they were used to a harsh environment and surviving on not much food, especially compared to rabbits that had been raised in cages in Europe,” Bruce said.

“A few years later people were expressing concerns that they’d done a bit too well and what are we going to do to control them.”

Across the next 80 years, using different ways to kill rabbits became an industry, with trappers often making good money.

“Pastoralists started talking about the need to introduce a communicable disease, especially because their rabbit control was so labour intensive,” Bruce said.

“But some people were nervous about whether it could also kill livestock and native animals.

“The argument bubbled away and then in the 1930s the CSIRO started doing research on myxomatosis.”

Other of the main aims Bruce had when writing his book was highlighting the contributions of hidden figures in the fight against rabbits.

“Jean Macnamara made a breakthrough in finding a cure for polio and while she was doing that research, she came across others doing work on myxomatosis,” he said.

“She urged the CSIRO to get serious about the research and she said they were doing research in the wrong place. She identified that you needed insects to carry the disease.

“Thanks to her work the virus did spread but she’s given very little credit for it.”

While myxomatosis went on to work well in wetter areas, it did not take hold in drier country because most of the time there were no mosquitoes to carry the disease. Eventually, calicivirus came in and was spread through fleas, which were not as dependent on water.

“At the time calicivirus was being developed, the leading researcher in the world on fleas was Miriam Rothschild, from the well-known banking family,” he said. “She worked out how a flea could transmit calicivirus.”

Bruce said one of the main messages of his book was that farmers could not rely on biological control.

“The rabbit will evolve to a stronger animal, the strongest survive the virus and they pass their genes on,” he said.

“This highlights the need to keep doing research – unless you’re doing that you’ll never get the next big breakthrough in rabbit control.”

- Details: Book available through Wakefield Press at wakefieldpress.com.au or call 08 8352 4455.